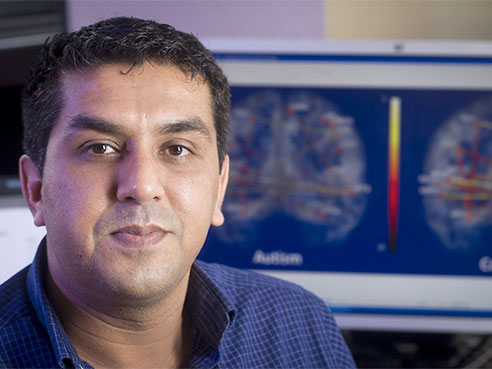

Ten weeks of intensive reading intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder was enough to strengthen the activity of loosely connected areas of their brains that work together to comprehend reading, University of Alabama at Birmingham researchers have found. At the same time, the reading comprehension of those 13 children, whose average age was 10.9 years, also improved.

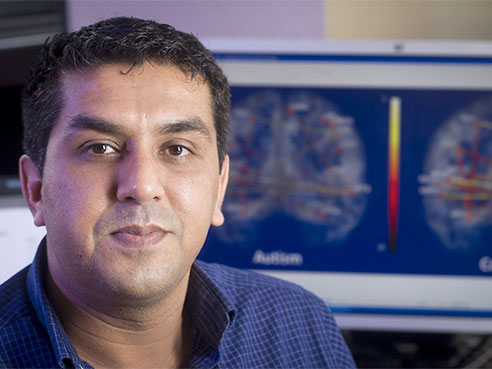

“This study is the first to do reading intervention with ASD children using brain imaging techniques, and the findings reflect the plasticity of the brain,” said Rajesh Kana, Ph.D., associate professor of psychology in the UAB College of Arts and Sciences and the senior author on this paper. “Some parents think, if their child is 8 or 10 years old when diagnosed, the game is lost. What I stress constantly is the importance of intervention, and the magic of intervention, on the brain in general and brain connectivity in particular.”

Rajesh Kana

Rajesh Kana

Families taking part in the study received the intensive intervention — which was four hours a day, five days a week, for a total of 200 hours of face-to-face instruction — free of charge, says Kana.

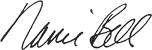

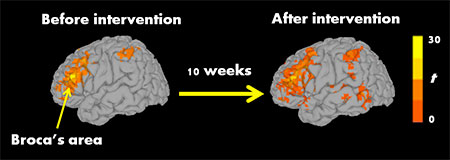

It is well-known that children with ASD have decreased connectivity between certain areas of the brain’s reading network, as compared with typically developing children. The children with ASD who received the 10-week reading intervention in Kana’s study improved their reading comprehension by modulating their brain function. They showed increased activation of the brain regions involved in language and visual/spatial processing in the left hemisphere of the brain — where language abilities reside — and also compensatory recruitment of some regions in the right hemisphere and regions of the brain beneath the outermost cortex.

Moreover, the amount of increased brain activation and functional connectivity of two core language areas — the left middle temporal gyrus and the left inferior frontal gyrus (which includes Broca’s area that enables a person to speak words) — correlated with the amount of improvement in reading comprehension for the intervention group of children with ASD.

“The ASD brain processing after intervention looks richer, with visual, semantic and motor coding that is reflected by more active visual activity and involvement of the motor areas,” Kana said.

Click to enlarge.

Change in functional connectivity for the experimental group of autism spectrum disorder participants as a result of the reading intervention. The functional connectivity of the Broca’s area with the rest of the brain and the change in connectivity from pre-to-post intervention during resting state show statistically significant changes in connectivity in the left hemisphere. The scale (right) represents significance in terms of T threshold.Altogether, these results support the use of specialized intervention for children with ASD to boost their higher-order learning skills, and they add to the growing evidence of the plasticity (ability to alter function) of the young brains in children with ASD. The translational neuroimaging in this study increases the understanding of established neural networks in children with ASD, and this knowledge will help develop future targeted behavioral interventions.

Control groups of matched typically developing children and children with ASD — both of whom did not receive reading intervention during the study period — showed no significant changes in connectivity in their brains or in reading comprehension at 10 weeks.

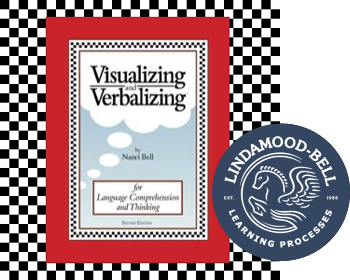

The Lindamood-Bell reading intervention used in the study teaches children to form concept images when they read and hear language. Such nonverbal sensory input can help develop the imagery-language connection in the brain, and it improves oral and reading comprehension, establishes vocabulary, and develops higher-order thinking skills. The intervention — called Visualizing and Verbalizing for Language Comprehension and Thinking — was administered at one of the 61 Lindamood-Bell Learning Centers nearest the families of the children with ASD. During the 10-week intervention, children with ASD get one-on-one instruction in a distraction-free setting, four hours a day, five days a week.

“People with autism are relatively better at visual/spatial processing,” Kana said. “The intervention facilitates the use of such strengths to ultimately improve language comprehension.”

The tool for collecting brain connectivity data is functional magnetic resonance imaging. The fMRI machine detected areas of the brain that were active by increased blood flow as the children performed a sentence comprehension task — answering whether a sentence was true or false. Since the intervention focused on using image concepts, the study used both high-imagery sentences, such as “An H on top of an H on top of another H looks like a ladder,” and low-imagery sentences, such as “Addition, subtraction and multiplication are all math skills.” Different parts of the brain in the intervention group showed increased activity or connectivity in response to the two types of questions.

Donna Murdaugh

Donna Murdaugh

Modern brain science recognizes that distinct areas of the brain have different, specialized functions — in computer terms, the brain functions through distributed processing. Two of the most famous of these distinct areas are Broca’s area, in the left frontal lobe, and Wernicke’s area, located where the left temporal lobe of the brain meets the parietal and occipital lobes. People with a stroke in Broca’s area can understand words, but they cannot speak; people with a stroke in Wernicke’s area can form words, but they cannot understand language.

In addition to the task-based fMRI, the UAB researchers used a different approach on the same groups of children — resting-state fMRI. This protocol looks at specific areas of the brain to see if those areas show activity during short time segments while the child simply rests inside the fMRI machine. That correlation in time is a measure of connectivity. The 16 children with ASD who received the 10-week reading intervention and completed the resting-state fMRI study had greater functional connectivity of Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas, as compared with their brains before the intervention. They also had greater connectivity between either the Broca’s area or the Wernicke’s area to the other parts of the brain that are recruited to compensate for the ASD underconnectivity. Furthermore, the strength of those connections correlated with the amount of reading comprehension improvement in the children who received reading intervention.

“By examining the reading network either during rest or during an active task, we get the opportunity to examine the same network under different levels of cognitive/linguistic demand,” said Kana. “This provides not only the basic spontaneous fluctuations of the reading network, but also how the network behaves under task demand.”

All of the children in the studies had reading tests, verbal IQ tests and fMRI at week 0 and week 10. The experimental children with ASD were given the reading intervention between those two test dates. The 13 children with ASD who were controls received their free reading intervention after the tests and neuroimaging were completed at 10 weeks.

Families were recruited across Alabama through support groups and clinics, and elsewhere in the United States through Lindamood-Bell Learning Centers. Out-of-state families came to Birmingham from the cities of Philadelphia, Houston, Chicago and Boston, and from elsewhere in Georgia, Minnesota, California, Hawaii, New Jersey and Florida for the tests and imaging. Each family had to stay at UAB for two days during the pre- and post-intervention studies.

The subjects in the study with ASD were high-functioning children who could read aloud well but had poor comprehension. To help the young children adjust before the neuroimaging, the researchers showed them the fMRI machine, let them lie in it and played the sounds the machine would make. On scanning day, the machine was decorated with colorful stickers to look like a toy, and the child was tucked in with a Mickey Mouse blanket.

The task-based study, “The Impact of Reading Intervention on Brain Responses Underlying Language in Children with Autism,” is published online in advance of print in the journal Autism Research. Co-authors are Donna Murdaugh, Ph.D., who did her graduate work at UAB and is now at Emory University School of Medicine, and Hrishikesh Deshpande, Department of Radiology, UAB School of Medicine.

The resting-state study, “Changes in Intrinsic Connectivity of the Brain’s Reading Network following Intervention in Children with Autism,” is published online in advance of print in the journal Human Brain Mapping. Co-authors are Murdaugh and Jose Maximo,UAB Department of Psychology.

Ensure nourishing meals, perhaps by having your child help with a weekly menu.

Ensure nourishing meals, perhaps by having your child help with a weekly menu.

Establish age-appropriate responsibilities.

Establish age-appropriate responsibilities. t Birmingham (UAB), in which a group of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) received 10 weeks of intensive instruction utilizing the Visualizing and Verbalizing for Language Comprehension and Thinking® program, found that the instruction “was enough to strengthen the activity of loosely connected areas of their brains that work together to comprehend reading.” The children’s reading comprehension also improved.

t Birmingham (UAB), in which a group of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) received 10 weeks of intensive instruction utilizing the Visualizing and Verbalizing for Language Comprehension and Thinking® program, found that the instruction “was enough to strengthen the activity of loosely connected areas of their brains that work together to comprehend reading.” The children’s reading comprehension also improved. Rajesh Kana

Rajesh Kana

Donna Murdaugh

Donna Murdaugh